| International Journal of Clinical Pediatrics, ISSN 1927-1255 print, 1927-1263 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Int J Clin Pediatr and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.theijcp.org |

Original Article

Volume 2, Number 2, December 2013, pages 68-73

Clinical Features of Acute Focal Bacterial Nephritis in Children

Katsuya Saitoa, Tatsuo Fuchigamia, c, Maki Hasegawaa, Yuki Kawamuraa, Koji Hashimotoa, Yukihiko Fujitab, Yasuji Inamoa, Shori Takahashia

aDepartment of Pediatrics and Child Health, Nihon University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan

bDivision of Medical Education Planning, Nihon University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan

cCorresponding author: Tatsuo Fuchigami, Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, Nihon University School of Medicine, 30-1 Oyaguchi-Kamicho, Itabashi-ku, Tokyo 173-8610, Japan

Manuscript accepted for publication October 11, 2013

Short title: Acute Focal Bacterial Nephritis in Children

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/ijcp115w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Acute focal bacterial nephritis (AFBN) is a localized bacterial infection of the kidneys. Patients present with an inflammatory mass without frank abscess formation, which may represent a relatively early stage of renal abscess. In children, most patients with AFBN present with non-specific findings of fever and flank or abdominal pain.

Methods: From 2008 to 2011, AFBN was diagnosed in 11 children at the Department of General Pediatrics, Nihon University Nerima Hikarigaoka Hospital, Tokyo, Japan. Clinical data of 11 cases (four girls and seven boys) with a mean age of 5.4 years (range 2-8 years) were available for retrospective evaluation.

Results: All children presented with fever and rapid deterioration of their clinical condition. Six children suffered from gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting and abdominal pain. Four children suffered from neurological symptoms, including meningeal irritation, unconsciousness, and seizure. In renal ultrasonography, abdominal findings were seen in four patients. However, abdominal enhanced computed tomography (CT) was indispensible for diagnosis of AFBN in these patients.

Conclusions: We recommend that abdominal enhanced CT should be performed for patients with fever of unknown origin. AFBN should be suspected in children with fever and rapid deterioration of clinical condition.

Keywords: Acute focal bacterial nephritis; Acute lobar nephronia; Neurological symptoms; Meningeal irritation; Brain edema; Fever of unknown origin; Abdominal enhanced computed tomography; Children

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Acute focal bacterial nephritis (AFBN) is a localized bacterial infection of the kidneys presenting as an inflammatory mass without frank abscess formation. It was first described in adults by Rosenfield et al in 1979 and called lobar nephronia analogous to lobar pneumonia [1]. AFBN is considered to be a midpoint in the spectrum of upper urinary tract infections, ranging from pyelonephritis to intrarenal abscess, and may represent a relatively early stage of renal abscess [2]. In children, most of the patients with AFBN presented with non-specific findings of fever and flank or abdominal pain. Pyuria, leukocytosis, and elevated C-reactive protein are also usually found. Some patients present only with fever and have minimal symptoms such as vague flank discomfort, malaise, or even no urinary symptoms, and rarely, a few patients may have no pyuria and negative urine culture [3, 4]. The pathogenesis of AFBN is not entirely clear. Septicemia due to respiratory tract infections or ascending infection of the lower urinary tract is suspected. Owing to different treatments, AFBN has to be distinguished from renal abscess. AFBN is a localized bacterial infection without abscess formation.

We analyzed clinical data of 11 children diagnosed with AFBN from 2008 to 2011 at the Department of General Pediatrics, Nihon University Nerima Hikarigaoka Hospital, Tokyo, Japan.

| Patients and Methods | ▴Top |

We retrospectively evaluated clinical data of 11 children diagnosed with AFBN from January 2008 to December 2011 at the Department of General Pediatrics, Nihon University Nerima Hikarigaoka Hospital, Tokyo, Japan. Four girls and seven boys with a mean age of 5.4 years (range 2-8 years) on admission were followed up for an average 2.8 years (range 0.1-3.4 years) to assess clinical features, predisposing factors, imaging techniques, treatment, and outcome.

All children received intravenous antibiotics after blood and urine cultures were taken. All children underwent either renal ultrasonography (US) or abdominal computed tomography (CT) to confirm the diagnosis. In addition, renal parenchymal perfusion was examined by color power Doppler US. The criteria for diagnosis of AFBN included: 1) renal US showing focal areas with poorly defined margins and decreased echogenicity; 2) focal areas of decreased perfusion on power Doppler US; or 3) solid, poorly margined areas of decreased enhancement on CT [5]. Ten children underwent voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) after successful antibiotic treatment.

| Results | ▴Top |

All children presented with fever and rapid deterioration of their clinical condition. Presenting symptoms on admission are summarized in Table 1. Six children suffered from gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting and abdominal pain. Four children suffered from neurological symptoms, including meningeal irritation, unconsciousness, and seizure. In the four patients with neurological symptoms, there were two with seizures, two with neck stiffness, and two with unconsciousness and mild brain edema, as observed on cranial CT. However, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings of all four patients were normal. In the two children with unconsciousness, consciousness returned to normal on the second day of admission. The electroencephalography (EEG) findings did not demonstrate high-voltage slow waves and epileptic discharges.

Click to view | Table 1. Presenting Symptoms and Laboratory Findings on Admission |

The main laboratory findings on admission are also summarized in Table 1. C-reactive protein (CRP; mean 11.34 mg/dL, range 4.67-19.13 mg/dL) and white blood cell count (WBC; mean 18,800/µL, range 10,200-41,200/µL) were raised in all children. Leukocyturia was found in five children and bacteriuria in six. Urine cultures were positive for Enterococcus faecalis (n = 4), Escherichia coli (n = 1), and Proteus sp. (n = 1) (Table 1). In three patients, leukocyturia and bacteriuria were found. However, in another three patients, neither leukocyturia nor bacteriuria was found. Urine β2-microglobulin (BMG) was high in five patients, and N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase (NAG) was high in eight. Both urine BMG and NAG were high in three patients. Both urine BMG and NAG were low in one patient.

All children underwent either renal US or abdominal CT to confirm the diagnosis. In renal sonography, abnormal findings were seen in four patients; there were three patients with mild hydronephritis, and one patient with a hypoechoic area in the kidney. This renal hypoechoic area also showed no perfusion on power Doppler US. Abdominal enhanced CT was indispensable for diagnosis of AFBN in these patients.

Ten children underwent VCUG. Five of these with AFBN revealed vesicoureteral reflux (VUR); one required surgical intervention for high-grade VUR, and the other four were managed without surgery. No kidneys entirely lost function or required removal.

All children received intravenous antibacterial therapy for a mean 11.8 days (range 5-31 days). Six patients were treated intravenously with cefotaxime sodium (CTX) monotherapy, one with panipenem/betamipron (PAPM/BP), two with CTX and ampicillin hydrate, one with CTX and PAPM/BP, and one with CTX and meropenem hydrate until bacterial culture and sensitivity results were known. If necessary, treatment was modified to the most appropriate agent. Intravenous therapy was followed by low-dose prophylactic antibiotics with cefaclor, cefcapene pivoxil hydrochloride hydrate, sulfamethoxazole trimethoprim, and amoxicillin hydrate for 3 weeks to 38 months (mean 51.6 weeks) until further investigations or treatment of the underlying cause was complete.

Case report

Patient 1

A 5-year-old boy experienced fever, vomiting, and diarrhea for 1 day before hospitalization. He visited a local clinic on the day of admission, and had a generalized seizure at the clinic. Although he returned home, he had another generalized seizure, and he was transferred to the Department of General Pediatrics, Nihon University Nerima Hikarigaoka Hospital, Tokyo, Japan. He had a febrile seizure at 4 years of age. At admission, his general condition was poor. He had somnolence, and his level of consciousness was open eye to speech. He had neck stiffness. Deep tendon reflex was normal. Costovertebral angle pain and tenderness were not recognized.

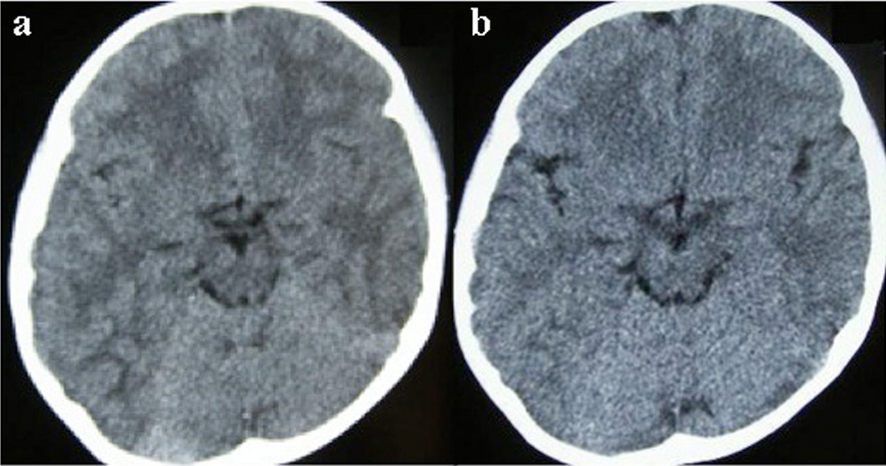

Laboratory findings on admission were WBC 41,200/µL and CRP 9.51 mg/dL. Urinalysis was negative for protein, occult blood, and leukocyturia. However, urine BMG was high at 17,500 µg/L and NAG was high at 26.9 U/L. Although he had neck stiffness, CSF analysis did not show any pleocytosis, elevation in protein, or reduction in glucose. Blood, CSF, and urine cultures showed no pathogens. Cranial CT revealed mild brain edema on the day of admission. However, brain CT on the fifth day after admission did not show edema (Fig. 1). On the day of admission, neck stiffness, seizure, unconsciousness, and mild brain edema on CT strongly suggested that he was affected with acute encephalopathy.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Brain computed tomography (CT). (a) On admission. CT showed cerebral edema, but the midline structure did not undergo a shift. (b) Five days after admission. CT showed improvement of cerebral edema. |

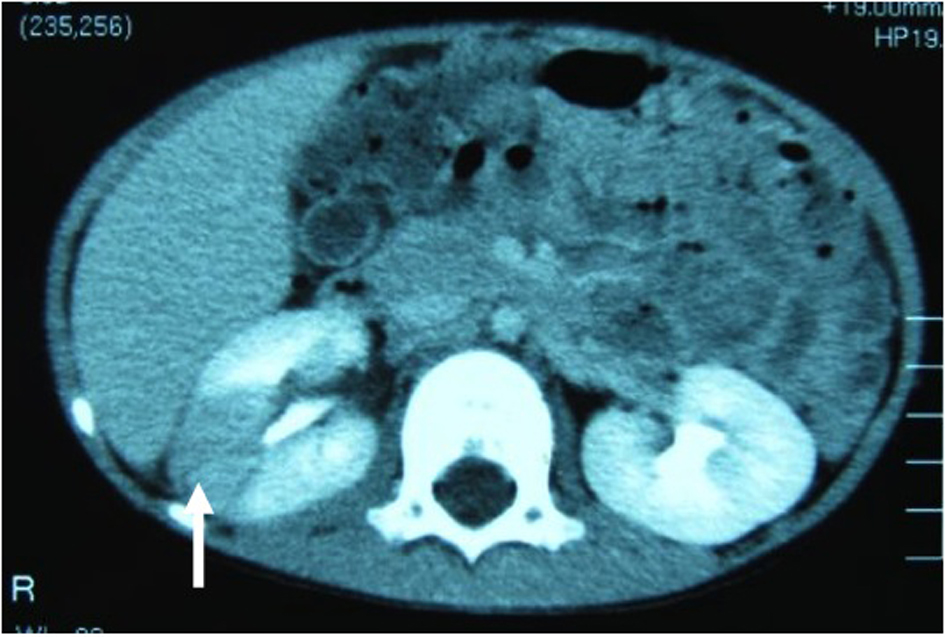

The patient was treated with intravenous osmotic diuretic and isotonic fluid infusions. After treatment, the EEG findings did not demonstrate high-voltage slow waves and epileptic discharges. The patient was also treated with intravenous CTX and PAPM/BP because the origin of his fever was suspected to be urinary tract infection and/or sepsis. Although several cultures, including urine, showed no pathogens, urine BMG and NAG levels were high, and renal sonography showed a hypoechoic area in the right kidney. These findings indicated AFBN, and abdominal CT was performed. Abdominal enhanced CT showed enlargement of both kidneys, with multiple wedge-shaped defects (Fig. 2) [6]. Technetium 99m dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) scintigraphy was performed and revealed generalized atrophy and a corresponding area of decreased tracer uptake in the right kidney and enlargement of the left kidney. Findings from both CT and DMSA scans confirmed the diagnosis of AFBN. He was discharged after antibacterial therapy for about 1 month. After discharge, he was followed up at our hospital, and VCUG showed grade 1 bilateral VUR. He was managed without surgery.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Abdominal enhanced computed tomography (CT). CT showed enlargement of both kidneys, with multiple wedge-shaped defects. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Seidel et al reported that all children with AFBN were admitted with septic temperatures and rapid clinical deterioration [7]. The most common presenting symptoms included high fever followed by flank or abdominal pain. Shinoda et al reported that 34 Japanese children with AFBN had fever (100%), flank or abdominal pain (47%), and non-specific symptoms such as appetite loss (38%) [8]. In our study, there were four patients with neurological symptoms, including meningeal irritation, unconsciousness, and seizure. Reports of cases of AFBN with neurological symptoms are rare. There have been three reports of pediatric cases of AFBN with meningeal irritation in Japan [9, 10]. Komatsu et al reported two older children (a 12-year-old boy and a 13-year-old girl) with AFBN initially suspected of meningitis due to severe extrarenal symptoms [9]. Yamamoto et al also reported a 4-year-old boy with AFBN associated with bladder diverticular, presenting with meningeal irritation [10]. These three patients’ CSF analyses did not show any pleocytosis, elevation in protein, or reduction in glucose, and CSF cultures showed no pathogens.

Kline et al reported a 6-year-old girl with AFBN who was admitted to hospital with cyanosis, hypotension, and disorientation [11]. She was well until the day before admission when she developed headache and high fever. On the morning of admission, she had a 2-3 min generalized convulsion. Her CSF analysis showed 25 white blood cells/µL (97% mononuclear and 3% polymorphonuclear cells), 703 red blood cells/µL, and protein and glucose levels of 14 and 162 mg/dL, respectively. Blood and urine cultures yielded E. coli. However, CSF culture showed no pathogens. The patient’s clinical status improved during the initial 24-h hospitalization. CSF obtained on the fifth day of hospitalization was normal. The authors had no definite explanation, except perhaps as related to sepsis and parameningeal inflammation and prolonged seizure activity.

Akiba et al also reported an 8-year-old boy with AFBN associated with acute encephalitis/encephalopathy [12]. He had high fever, unconsciousness, and general tonic-clonic convulsions during about 10 min on the day of admission. He had neck stiffness. His CSF analysis showed a WBC of 5/µL, and protein and glucose levels of 18 and 93 mg/dL, respectively. Urine culture yielded Enterococcus sp. However, CSF and blood cultures showed no pathogens. Brain CT revealed mild brain edema. Interleukin (IL)-6 in the CSF and interferon (IFN)-γ in the serum were found to be high at 1,988.7 pg/mL (normal, < 9.7 pg/mL) and 819.7 pg/mL (normal, < 42.9 pg/mL), respectively. The authors concluded that such high levels of IL-6 and IFN-γ suggested significant inflammation of the central nervous system due to viral infection. Clinical manifestations of this case were similar to our cases. However, we did not measure IL-6 and IFN-γ levels. Fujiwara et al reported four pediatric cases of mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion (MERS) accompanying AFBN [13].

MERS was identified by Tada et al in 2004 as a new type of acute encephalopathy. MERS is characterized by transient splenial lesions with high-signal intensity on diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging, a mild clinical course, and a good outcome [14]. It is proposed that MERS may be caused by intramyelinic axonal edema or local inflammatory cell infiltration. MERS has been associated with various infectious diseases. Influenza virus A and B are the most common pathogens, followed by mumps virus, adenovirus, rotavirus, streptococci, and E. coli in Japan [15]. We have also reported cases of MERS associated with rotavirus and mumps virus infections [16-18]. Although there are many reports of virus-associated MERS, bacterial infections as the cause of MERS seem to be rare. Therefore, the four pediatric cases of MERS accompanying AFBN reported by Fujiwara et al were of particular interest, and bacteriuria with E. coli was found in two of these four children.

Cheng et al reported that E. coli was the most common pathogen cultured from 59 of 61 urine samples from 80 patients with AFBN, which was consistent with previous results [3]. In our study, leukocyturia (five patients) and bacteriuria (six patients) were found in 11 children with AFBN. However, Ent. faecalis (4/6 cases) was the most common pathogen, and E. coli was the only positive culture from urine samples.

US is the best screening and diagnostic method for evaluation of renal inflammatory disease in the pediatric population [19]. However, both false-positive and false-negative findings have been reported [20]. By US, AFBN usually presents as an ill-defined focal mass with varying echogenicity. Depending on the stages of AFBN, sonographic features range from iso- to hypo- or hyperechogenic lesions [3, 21]. The sensitivity of US would be markedly improved if both nephromegaly and a focal mass were observed [22]. However, there were 7/11 false-negative findings by US in our study. CT with contrast is considered to be the gold standard for diagnosis of AFBN and typically displays poorly enhanced solid wedge-shaped defects with macrostriation [20, 22].

In general, 2-3 weeks antimicrobial therapy tailored to the urinary pathogens is recommended for patients with AFBN [5, 11, 19, 21, 23]. Cheng et al also suggested that 3 weeks intravenous and oral antimicrobial therapy should constitute the treatment of choice for all patients with AFBN [3]. Our patients were treated intravenously with antibacterial therapy for an average 11.8 days (range 5-31 days), followed by an oral antibiotic prophylaxis for an average 51.6 weeks (range 3 weeks to 38 months). Antibacterial therapy of our patients was in accordance with the recommendation of Cheng et al for the treatment of AFBN [3].

In conclusion, abdominal enhanced CT is indispensable for the diagnosis of AFBN. Hence, we recommend that it should be performed for patients with fever of unknown origin. AFBN should be suspected in children with fever and rapid clinical deterioration.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Rosenfield AT, Glickman MG, Taylor KJ, Crade M, Hodson J. Acute focal bacterial nephritis (acute lobar nephronia). Radiology. 1979;132(3):553-561.

pubmed - Cox SM, Cunningham FG. Acute focal pyelonephritis (lobar nephronia) complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71(Suppl 3 Pt 2):510-511.

pubmed - Cheng CH, Tsau YK, Lin TY. Effective duration of antimicrobial therapy for the treatment of acute lobar nephronia. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):e84-89.

doi pubmed - Moriuchi M, Nagasawa Y, Ishikawa T, Saito K, Hashimoto K, Fuchigami T, Inamo Y. Two pediatric patients with acute focal bacterial nephritis. J Nihon Univ Med Ass. 2009;68(5):297-300. [Japanese].

doi - Uehling DT, Hahnfeld LE, Scanlan KA. Urinary tract abnormalities in children with acute focal bacterial nephritis. BJU Int. 2000;85(7):885-888.

doi pubmed - Saito K, Fuchigami T, Hasegawa M, Imai Y, Hashimoto K, Fujita Y, Inamo Y, et al. Four cases of acute focal bacterial nephritis with neurological symptoms. J Nihon Univ Med Ass. 2012;71(4):273-277. [Japanese].

doi - Seidel T, Kuwertz-Broking E, Kaczmarek S, Kirschstein M, Frosch M, Bulla M, Harms E. Acute focal bacterial nephritis in 25 children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22(11):1897-1901.

doi pubmed - Shinoda G, Haruta T, Maeda H, Kobayashi K, Kuroki S, Kubota M, Nishio T. A pediatric case of acute focal bacterial nephritis; comparison with the reports in Japanese child cases. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 2001;75(11):981-988. [Japanese].

pubmed - Komatsu H, Yutaka N, Kinoshita D, Kudou N, Kotani M, Yoshida T, Asazuma Y, et al. Report of two elder children with acute focal bacterial nephritis initially suspected of meningitis due to severe extrarenal symptoms. Japanese J Pediatr. 2003;56(7):1534-1538. [Japanese].

- Yamamoto S, Miura Y, Iseki K. A case of acute focal bacterial nephritis associated with bladder diverticula presenting with meningeal irritation sign. J Clin Pediatr Sapporo. 2005;53(1-2):15-18. [Japanese].

- Kline MW, Kaplan SL, Baker CJ. Acute focal bacterial nephritis: diverse clinical presentations in pediatric patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1988;7(5):346-349.

doi pubmed - Akiba T, Ikeda H, Kanai M, Sasa S, Toriyabe M, Sakamoto M, Ichiyama T. A child case of acute focal bacterial nephritis associated with acute encephalitis/encephalopathy. Japanese J Pediatr. 2005;58(5):839-842. [Japanese].

- Fujiwara Y, Tanaka F, Wakamiya T, Kobori T, Hashiguchi K, Sato M, Arai C, et al. Four cases of mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion (MERS) accompanying acute focal bacterial nephritis (AFBN). J Jpn Pediatr Soc. 2012;116(12):1880-1885. [Japanese].

- Tada H, Takanashi J, Barkovich AJ, Oba H, Maeda M, Tsukahara H, Suzuki M, et al. Clinically mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion. Neurology. 2004;63(10):1854-1858.

doi pubmed - Takanashi J. Two newly proposed infectious encephalitis/encephalopathy syndromes. Brain Dev. 2009;31(7):521-528.

doi pubmed - Arakawa C, Fujita Y, Imai Y, Ishii W, Kohira R, Fuchigami T, Mugishima H, et al. Detection of group a rotavirus RNA and antigens in serum and cerebrospinal fluid from two children with clinically mild encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2011;64(3):204-207.

pubmed - Kimura K, Fuchigami T, Ishii W, Imai Y, Tanabe S, Kuwabara R, Fujita Y, et al. Mumps-virus-associated clinically mild encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion. Int J Clin Pediatr. 2012;1(4-5):124-128.

- Fuchigami T, Goto K, Hasegawa M, Saito K, Kida T, Hashimoto K, Fujita Y, et al. A 4-year-old girl with clinically mild encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion associated with rotavirus infection. J Infect Chemother. 2013;19(1):149-153.

doi pubmed - Klar A, Hurvitz H, Berkun Y, Nadjari M, Blinder G, Israeli T, Halamish A, et al. Focal bacterial nephritis (lobar nephronia) in children. J Pediatr. 1996;128(6):850-853.

doi - Soulen MC, Fishman EK, Goldman SM, Gatewood OM. Bacterial renal infection: role of CT. Radiology. 1989;171(3):703-707.

pubmed - Rathore MH, Barton LL, Luisiri A. Acute lobar nephronia: a review. Pediatrics. 1991;87(5):728-734.

pubmed - Cheng CH, Tsau YK, Hsu SY, Lee TL. Effective ultrasonographic predictor for the diagnosis of acute lobar nephronia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23(1):11-14.

doi pubmed - Boam WD, Miser WF. Acute focal bacterial pyelonephritis. Am Fam Physician. 1995;52(3):919-924.

pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

International Journal of Clinical Pediatrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.