| International Journal of Clinical Pediatrics, ISSN 1927-1255 print, 1927-1263 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Int J Clin Pediatr and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.theijcp.org |

Case Report

Volume 5, Number 3-4, December 2016, pages 54-55

Primary Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Infancy With Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection: A Case Report

Elie Choueirya, b, Carla El Haberb, d, Sandy Diabb, Paul Henry Torbeyb, c, Bernard Gerbakaa, b

aPediatric Intensive Care Unit, Department of Pediatrics, Hotel Dieu De France Hospital, Beirut, Lebanon

bDepartment of Pediatrics, Hotel Dieu De France Hospital, Beirut, Lebanon

cPediatric Pulmonary Unit, Department of Pediatrics, Hotel Dieu De France Hospital, Beirut, Lebanon

dCorresponding Author: Carla El Haber, Department of Pediatrics, Hotel Dieu De France Hospital, Bd. Alfred Naccache, Achrafieh, Lebanon

Manuscript accepted for publication December 02, 2016

Short title: Primary Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Infancy

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/ijcp261w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

A worldwide re-emergence of tuberculosis in infants has been observed during the last decade. Endothoracic tuberculosis predominates. However, few studies of infants with tuberculosis appear in the recent literature. As early diagnosis and treatment appear to prevent complications and reduce mortality, pediatricians should be alert for tuberculosis in infants with an atypical picture suggestive of infection. We report a 5-month-old Lebanese female infant, living in Abidjan, who presented first with non-productive cough treated as pneumonia without clinical improvement, and diagnosed later on as primary tuberculosis. This case highlights the rare presentation of tuberculosis in infancy and the co-infection of respiratory syncytial virus. We describe the features, clinical diagnosis, and management of this case.

Keywords: Tuberculosis; Infant; Respiratory syncytial virus; BCG

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The diagnosis of tuberculosis is more difficult in children, especially when symptoms are often subtle, chest images are less specific, standard sputum samples can rarely be collected, and children have lower bacterial loads, making mycobacterial recovery more difficult. Infants and young children are at much more risk of developing disseminated infection after primary tuberculosis and particularly tuberculous meningitis, which has the highest mortality rate. Child-to-child transmission is rare because of lower bacterial loads. Children usually acquire infection from infected parents or household contacts, so family and close contacts should always be screened [1].

| Case Report | ▴Top |

The patient was a 5-month-old girl from first-degree consanguineous parents born by cesarean section at full term, living in Abidjan. She was admitted to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for 6 days for meconium aspiration. Vaccination was done at birth.

One week before her travel to Lebanon, she developed an isolated non-productive cough. A chest radiography was done (image not available) in Abidjan and showed upper left lobe pneumonia treated by amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 75 mg/kg/day and betamethasone 0.5 mg/kg/day for 5 days. The housekeeper also presented with episodes of productive cough not investigated. There was no other relevant history. Given worsening of cough despite treatment and aggravation of signs of respiratory distress, she was transferred to Lebanon where she was hospitalized at Hotel Dieu De France Hospital.

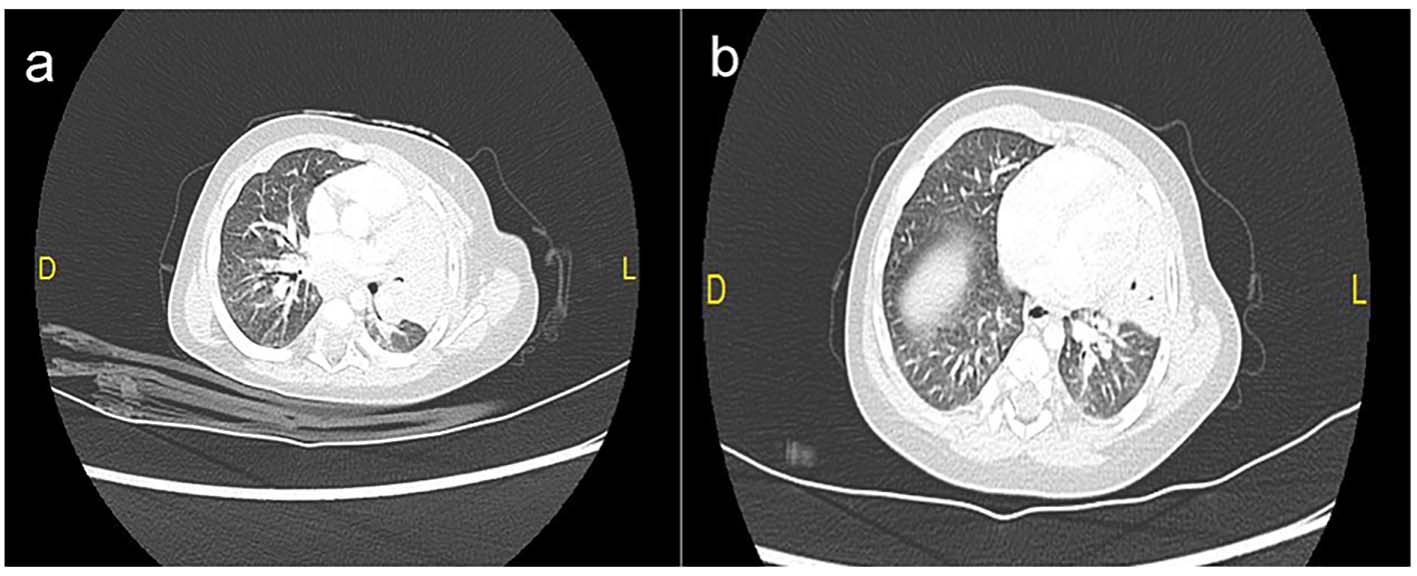

On physical exam, the infant was tonic and reactive, and showed no cervical, axillar or inguinal lymph nodes, no wheezing, and no hepatosplenomegaly. There were no signs of respiratory distress. All lab tests were normal. Mantoux skin test (5TU PPD) was positive and showed local induration of 20 mm with erythema. A chest radiography revealed parahilar and left lower lobe lung condensation (Fig. 1). Pulmonary computed tomography showed large left hilar lymphadenopathy, with central necrosis and multiple mediastinal lymph nodes in the paratracheobronchial region < 12 mm in diameter. No pleural or pericardial effusion was shown (Fig. 2). Gastric fluid aspirates showed identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis through Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast stain and culture on Lowenstein-Jensen. Two days after admission, she developed fever and nasal aspirate was positive for respiratory syncytial virus. Lumbar puncture was negative for M. tuberculosis. Bronchoscopy, ophthalmologic exam and abdominal ultrasonography were advised but refused by the mother due to financial issues. The patient was treated with isoniazid 75 mg/day, rifampin 150 mg/day and pyrazinamide 200 mg/day for 6 months. Following discharge to Abidjan, the mother was taught to follow monthly at the out-patient clinic until completion of treatment. Investigation of family and contacts for tuberculosis was advised for her close contacts in Abidjan.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Hilar and lower left lung condensation. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. (a, b) Pulmonary computed tomography showing hilar and lower left lung condensation, big left hilar lymphadenopathy, multiples lymph nodes with central necrosis and multiples mediastinal lymph nodes in the paratracheobronchial region < 12 mm in diameter. No pleural or pericardial effusion was shown. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

In tuberculosis endemic areas such as South Africa, bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccination is given within days of birth. It protects against disseminated tuberculosis in young children, and significantly reduces the risk of tuberculosis by 50%. However, BCG vaccination provides incomplete protection against tuberculosis in infants [2, 3]. Infants have a 50% risk of disease following exposure through transmission from an infectious adult family member compared to less than a 5% risk of disease in older children. The course of tuberculosis in infants differs from older children and adults, because progressive primary disease is more frequently seen in young infants while pleural effusions are uncommon [4]. Miliary spread and meningitis are more common in infants than in older patients [5]. Children under 3 years old have a high mortality rate due in part to the diagnostic difficulty of tuberculosis, as well as the increased rate of progressive disease and central nervous system involvement [5, 6]. Clinical diagnosis of tuberculosis in an infant is challenging because infants may present with non-specific findings such as reduced playfulness, fatigue, wheezing, non-remitting cough, failure-to-thrive or hepatosplenomegaly [7]. In infants who are more acutely ill, tuberculosis may be suspected on failure of first-line antibiotics [3]. Intradermal skin testing, the hallmark screening test for older children and adults, is less reliable in infants due to immature immune response. In our case, mild respiratory symptoms were present and Mantoux skin testing was positive. Communicable diseases and public health implications are also an important part of forensic pathology practice.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

| References | ▴Top |

- Pavithra Logitharajah, Beate Kampamann. Tuberculosis in children. Student BMJ Archive. Accessed 3 June 2009.

- Nelson LJ, Wells CD. Tuberculosis in children: considerations for children from developing countries. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2004;15(3):150-154.

doi - Hesseling AC, Rabie H, Marais BJ, Manders M, Lips M, Schaaf HS, Gie RP, et al. Bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine-induced disease in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected children. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(4):548-558.

doi pubmed - Cruz AT, Starke JR. Clinical manifestations of tuberculosis in children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2007;8(2):107-117.

doi pubmed - Marais BJ. Tuberculosis in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2008;43(4):322-329.

doi pubmed - Kinney HC, Thach BT. The sudden infant death syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(8):795-805.

doi pubmed - Vallejo JG, Ong LT, Starke JR. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of tuberculosis in infants. Pediatrics. 1994;94(1):1-7.

pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

International Journal of Clinical Pediatrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.